Someone asked when I visited the Gambia, “which one of your parents is white?” It wasn’t a question to cause offense, but a question to clarify a reality. My skin is light. It is obvious to an African that I am not— simply black.

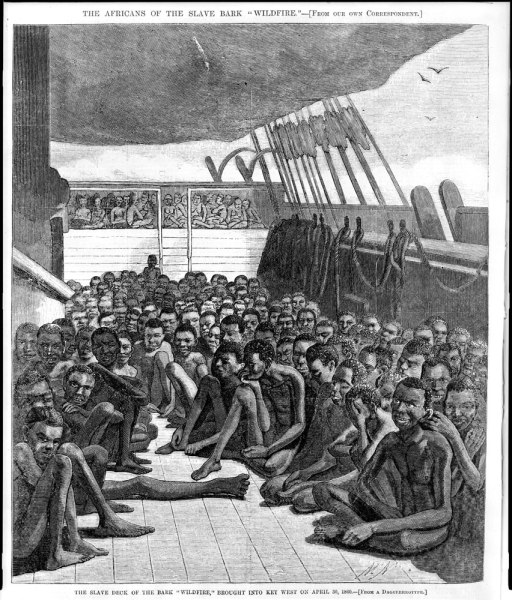

If you don’t know, The Gambia is a country on the West Coast of Africa. It is the place where Kunta Kinte of Alex Haley’s book Roots was stolen. Kinta was a young man who lived in Juffre a village on the edge of the Gambia River. I have visited the village and traveled to the small island where they held captured Africans before they were placed sardine like in ships and taken far away from home. Because of Roots, Gambians are very aware of the Trans-Atlantic slave trade. They understand it as very much a part of their history.

The question that I was asked in the Gambia would never be asked in the United States, where those captured Africans landed. The reasoning being is because of course I am Black and my parents are black and my grandparents are black. Because we have African ancestry. Yet, if this is the reality, then tell me why my skin lacks the deep dark brown tones of Africa?

Yes, I am beginning to talk about race. In this conversation I want to be clear that race is a social construct. It was constructed to make easy the enslavement of those with dark skin. It was constructed to ensure that those who were in similar positions of servitude and poverty didn’t come together to challenge those in power.

Much of this as a child of the 1960’s, I never fully learned in school. While the history of the U.S. is wrought in pain, injustice and suffering of those taken from the continent of Africa to build a country without compensation, our education systems, or at least the one I grew up in doesn’t tell the story of the origins of race. It has just been as I have gone back to school as a single-parent that I begin to read, learn and research these issues.

Our educational system never tells the full story of the many African women who were taken advantage of, abused and mistreated. Many of these women bore children whose light skin reminded them of their white captors. Yet, these children were not discarded, they were raised and loved and nurtured in the Black community.

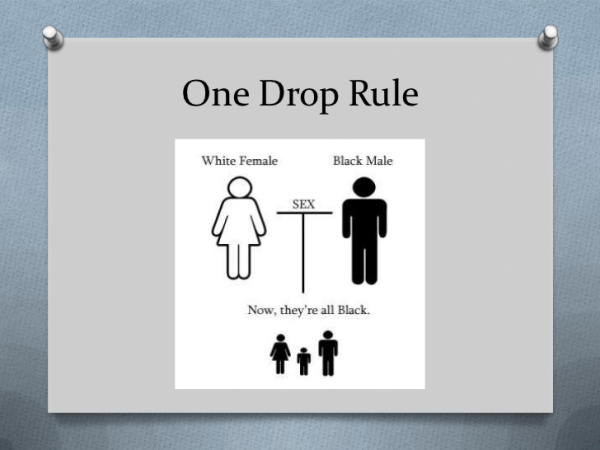

Many times when these children were born they were abandoned or sold by their white fathers and laws were created to make sure they could never claim their full heritage or inheritance. One such law was the “one drop rule.” This rule also known as the “one Black ancestor rule” means that anyone with known African ancestry is considered Black. No matter the tone, complexion or shade of skin, no matter the straightness of hair, if you can be connected to, if you are known as a descendant of someone — anyone — who has African ancestry in the United States of America you are black.

This is the story of my family and millions of families like mine, those who bear the skin of those who held Africans captive, yet were never allowed to participate in the fullness of life offered to those with white skin.

So the answer to the question posed to me in the Gambia is a great, grandparent … on both maternal and paternal sides of my family was probably white. And because of them in Africa, I am asked this question. It is a question of where are you from and to whom do you belong. It begs the question: why are you beige?